- Home

- Logan Noblin

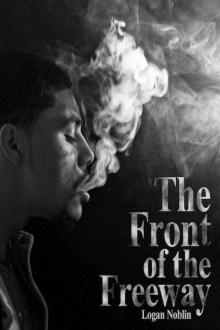

The Front of the Freeway Page 2

The Front of the Freeway Read online

Page 2

—Jiddu Krishnamurti

Grand Central Liquor is the bombed-out skeleton of a 1945 Berliner’s home. From behind two cutouts in the decaying concrete walls drip a multicolored cascade of beer bottles and fifths of cheap liquor, leaving the display windows something like the stained glass eyes in the ruins of a macabre cathedral. I’m sitting outside like a drunken minister, baptizing myself in 40 ounces of Mickey’s, two gulps at a time, from a squat glass bottle of olive green. And maybe my holy water is toxic, but it’s beautiful, and it’s friendly, and I’m not going to have to wash it when I’m done.

Its 12:30 and a belt of street lights is the only constellation in the grey Los Angeles night. It’s 12:30 and Tony’s late. I tilt my head and squint at my watch out of my right eye, but thirty minutes pass and Godot’s a no show. Alright, Tony, if I’m going to be drunk in public, I’m going to do it somewhere more interesting than this wreck. I scoop myself off the cement and start staggering down Jefferson, but before I can wipe the beer from my lips, a charcoal grey Oldsmobile slips out of the night like an alley cat creeping from lamp post to lamp post, rolling slowly towards me. Before I can move, the grey four-door eases next to me on the curb, and a fog-glazed window sinks into the sleek machine’s purring frame. A dense cloud of smoke puffs out through the window. There in the driver’s seat is the Cheshire Cat—a, big dumb crescent of Tony’s teeth staring right back at me through the haze.

“What’s up JT?” Tony’s in a good mood. Actually, Tony’s jubilant. Sitting in a cloud of thick, syrupy smoke that scrap metal matchbox might as well be the Batmobile. “Come on man, we’re late.” We’re late? We are nothing. I am drunk. You are late. I slide into the car thinking inebriated daggers at Tony, but lately I’ve been about as outspoken as a mime.

But for now, that’s just fine with Tony. We slip silently into the starless night under the hum of his big grey cat, imagining pensive nothings onto the fog-kissed canvas around me. Tony turns up the radio, and I watch long white webs of light dance out from the street lamps to the deep, droning bass hammering through the smoke and haze.

Bump. The rutted pavement of a concrete bridge shakes me awake. Suddenly, Tony and I both realize that I have no idea where I am. I sit up to check the world outside for a landmark, but find nothing except the black filth bubbling up through the dense, murky trail of the Los Angeles River.

“You lied to me, JT,” Tony coughs, coolly killing the machine’s melodic, pounding heartbeat with a brush of the volume dial. “When you told me it was alright. But it’s really not alright, is it?” Tony and I must be seeing different roads, because he’s winding between lanes in a short metal snake. “You work like a slave, man. How much are they paying you?”

“You know how much they’re paying me, Tony. Where are we going?”

“Come on, how much are they paying you, JT?”

“Eight an hour, same as you.”

“Eight an hour! Eight an hour, now ain’t that some shit?”

“Yeah, that’s some shit, Tony. Where are we?” Tony pinches the last of a white paper stem to his lips and lets it crackle to his fingertips, straining to hold his breath, before opening the window a slit and flicking it to the street.

“Eight dollars an hour… Doesn’t matter who you are, you can’t do shit with eight dollars an hour, man. No one can be happy with eight dollars an hour. What do you think, JT, do I look happy?” Tony looks like a dizzy black snowman with tomatoes for eyes.

“Sure, Tony. You look alright.” I can’t tell if Tony’s pulling over or swerving again, but in the last breaths of light pulsing meekly from a dying street lamp, I can see the sidewalk rippling like a mirage, crawling with the hustle of a trillion busy cockroaches. Then Tony is parking.

“Yeah…yeah, I’m alright. Yes sir, matter of fact, I got a second job.” I try to look surprised, but my suddenly enormously heavy head just rolls to my shoulder to give Tony a sideways look. But… “Yeah, I know, Romeo says we’re not supposed to work anywhere else or whatever. But, you know, I’m an entrepreneur. And an entrepreneur like myself needs a little room for maneuverability in my career. Diversify my bonds or some shit. So anyway, I started my own business. And if you’ll follow me,” Tony’s Cheshire smile is back, a toothy ghost haunting his lips, “I’d like to show you to my office.”

“A Poet makes himself a visionary through a long, boundless, and systematized disorganization of all the senses. All forms of love, of suffering, of madness; he searches himself, he exhausts within himself all poisons and preserves their quintessences… So what if he is destroyed in his ecstatic flight through things unheard of unnameable?”

—Arthur Rimbaud

I can’t help staring at my feet, thinking about squashing a hundred crawling lives. A hundred forgettable, trivial, six-legged lives. If they are God’s children, they are God’s abortions, and if I stomped on the sidewalk right now, it wouldn’t change a thing.

“JT, let’s go.” Tony’s severed head is gabbing from the cement, his body submerged in a concrete pit where the sidewalk sinks beneath Karen Residence Complex and cascades into the decaying remnants of a basement stairwell. Ten feet below street level, a locked and barred archway outlines Tony’s silhouette, coolly tracing the frame above for a key. A blink later my guide wrestles two inches of serrated steel into a doorknob, and Romeo’s Dissidents descend into Karen’s labyrinth. I bet the chipped mustard walls were painted a sterile white when they dug out the bottom floors in the sixties, but now the rotting, yellow plaster drips seamlessly down into the sweating, molding carpet. Tony glides to a halt before B33 and, with a wink, raps four knuckles of sharp percussion against the frail wood door. I dry my palms down the front of my jeans.

A bear in blue sweats and navy slippers tears open the door and wades into the hallway, crouching to squeeze his hulking cotton shoulders through the narrow doorframe. He pauses for a second, staring down from the ceiling into the shadowed hollow of Tony’s hood, but after a long, quiet moment, the bear erupts with a laugh of familiarity and scoops Tony off the ground in a steel-trap hug, Tony’s legs floundering like two ropes from his belt.

“Hey! Get the hell off me, Pauly!” Pauly couldn’t hear a plane crash over his own hooting, but he drops his friend and turns his perfectly round face on me.

“Who’s the white boy?” White boy, gringo. Dark used to be the absence of color, but now I think white is. It’s the absence of culture, community, home, or identity, and the proper historical backing to hold it all together. But it’s rootless, too, and without a pedigree to adopt or defend I’m perfectly neutral, perfectly homeless, and I never minded the anonymity.

“This is Julian. It’s cool, Pauly, he’s with me.” Pauly turns and stares down two bulging round cheeks at me, a thick, wrinkled brow framing two swollen white eyes, big as plates.

“Whatever you say, boss. What’s up man, I’m Paul.” I shake hands with a baseball mitt, a mass of smooth leather and nails like claws. “Come on now, get in here. The girls are waiting.” I step into the friendly murk of a cloud-choked apartment, tinged the same hue of vomit as the hallway. I follow Tony through the fog, but suddenly a hungry, clenching jaw is gnashing at my knees. “Kujo! Cool it!” Pauly snatches hold of three aluminum tags chiming below the bulldog’s wrinkled throat and jerks him from my calf, now a frozen flesh stump rooted in the faux wood tile. “Oh, don’t worry about him, he’s mostly harmless. Watch the teeth, though. Here, throw him one of these.” Pauly hands me a broiled pork peace offering and suddenly Kujo is cordial.

“Pauly, quit messing with that dog and check this out.” Tony’s furnished a karesansui garden of forest green and Ziploc pouches on the tiled kitchen counter and Pauly’s mouth is wetter than Kujo’s. “You know the stock, man, help yourself.” Blue bear buries a paw in the seam of his sweats and draws a thick roll of faded green. Walking his fingers to Jackson, he counts off more than my last paycheck.

“There’s Michael… Tito… Janet…and all their fucking cousi

ns, too. Here.” Tony the accountant is all smirking business. He rifles through the faded jade papers quietly and thrusts it deep in his denim thighs. Smiling, he brushes an ounce of counter moss into a cobalt Jansport.

“Alright, JT, let’s meet Jafar.” Jafar is a vegetarian. Jafar, coincidentally, is a hollow glass snake wound loosely on top of Paul’s living room table, gaping jaw flexed into a bowl, kernelled tail flicking wisps of smoke into the misty air. Jess, Paul’s neighbor, softly kisses the end of the smoking tail as her roommate, Melissa, holds a flame to his throat. Paul sags into a heavy, grey sofa chair and a brunette skeleton flutters into his lap. Hi, she’s Francie, and she’s pleased to meet you.

The tail spins clockwise while Jamaican drums hum somewhere in the background. Soon my lips are pressed tight to the warm serpentine rattle. I breathe deep while Melissa sets the little green forest ablaze, two fiery blue eyes fixed to mine under her rich, black eyelashes, fluttering gently across the table. After a few seconds, the green embers are burning holes through my ribs and I lean back, letting the fog roll off my lips. Melissa leans across the table and pulls the tail to her mouth, and, with a quick wink and half a smile, drags on the pipe until the bonsai bowl turns black.

“Guess what, Tony,” Francie chirps from Pauly’s blue, sofa chair lap. “Me and Pauly are pregnant!”

“What, again?” Pauly’s a grimace behind his beaming, twittering bride. “Damn, Pauly, isn’t this like your fifteenth kid?”

“Shut the fuck up, Tony.”

“Maybe you should wrap it the fuck up, Pauly!”

What’s tomorrow, Wednesday? I hate Wednesdays. The dishes are one thing, but an undersized Ecuadorian barking in your ear at six in the morning has its own place in hell.

“Where’ve you been, Tony? We missed you.”

Jess is rubbing Tony’s shoulders, now, laughing gently through the fog, her painted nails flashing like rubies around his neck and on his chest. He leans back and whispers across her cheek. She laughs again, softer this time from the back of her throat, gently biting at her bottom lip as her grip tightens around his shoulders.

“You work with Tony?” Francie offers, chin perched delicately on her fist, nose curled to a perfectly hooked beak.

“Yeah, we work at the same place.” Mellissa leans forward and plucks five clear shot glasses out from under the table, still streaked and beaded with the honey-yellow sweat of five swallowed whiskey shots. Pauly stretches behind the sofa and passes her a half-empty plastic bottle and she carefully drowns the glasses with the thin blonde syrup, sliding them around the table on the points of her fingers. “You used to work with him or something, Pauly?”

“Nah, me and Tony have known each other a real long time,” Pauly starts, shifting Francie from one bulging, blue knee to the other as he reaches for a glass. “We don’t work together, though. I’m a cop.”

“That’s right, ‘protect and serve,’” Francie giggles, proudly tracing an imaginary badge in the center of his sagging blue sweatshirt. Another cop, another empty plastic bottle. There’s no History Channel, but he’s up to the same trick, drowning the monotony of the day with one pale-gold toxic shot after another. And I get it, washing away in the night the agonizing repetition of the day, but for my father, it’s drowning him, too. He was soaking in it when my mother left, and he’s sinking even faster now, and the biting stench of the fermented fumes only turns my stomach. But who can blame him? It’s his escape, his quiet moment outside the insanity of routine, and I wouldn’t mind slipping out myself, if only for the night. And besides, I followed Tony this far from Romeo’s walls, and into the charming gloom of Pauly’s apartment, I’m suddenly eager to see how far from that cell he can take me.

Melissa slides out of her chair and eases softly next to me on the couch, and I do my best not to notice the stiff cuff of a lime green bra rounding over the top of her shirt as she hands me a glass. With a soft clink and a long nod, I empty the cup into my mouth as my lips and throat numb with the dry, lingering burn of the alcohol. After a few nauseous seconds pushing whiskey vapor through my nose, the numbness sets into my arms and legs, too, the weight of Jafar’s smoke washing through my blood, warping my vision. In the smiling haze filling Pauly’s apartment I’m starting to forget about working tomorrow or facing my father at home. Rodrigo, the kitchen, my house—they’re all slipping quietly into the dense, shifting cloud as the chemicals set in and the anxious, squirming knot in my stomach slowly unwinds.

“‘Protect and serve,’” Tony mocks from across the table, twisting his face away from Jess’s fingers gently tracing his pointed jaw. “You know my problem with cops? You guys always do what you’re told. You always say, ‘sorry, man, just doing my job’ because you have a lieutenant to answer to, and the lieutenant has a captain, and even the captain has some asshole breathing down his neck.” Francie rolls her eyes, sighing loudly as Pauly takes a patient drag from the mouth of the plastic bottle, agitated bubbles gushing from his lips into the double-distilled gasoline. “You’re not even people, you’re Robocops. No faces, just helmets and shades. Look at your badge, man, you’re a number, and your boss is protecting and serving himself. That’s the whole joke, and they got the punch line pinned to your jackets.”

“We all have our assholes. We all have our bosses,” Pauly coughs, wincing against the honeyed burn still glistening on his lips. “But we all have to get paid, too.” Tony’s squinting, irritated scowl creases to a narrow, satisfied grin as he slides a Ziploc square bulging with dried green clover off the table between two fingers.

“Yes we do, but that doesn’t mean we have to be machines. Self-employment,” he gloats, gingerly shaking the plastic stamp next to his cheek. “The only asshole I have to answer to is me.”

“Both of you shut up, we’re supposed to be relaxing, and I don’t want to hear about work,” Francie snaps, rotating Jafar with an outstretched finger until I’m staring straight down the eye of a gnarled glass tail. A second later, Melissa’s feeding the snake the hot, orange flame of a short Bic lighter as I swallow smoke, the world around Jafar tilting and bending in the pale lamplight. I lean back to push the fog from my lungs, but it catches in my throat and fires out in a fit of dry, heaving coughs, thin gusts of cloud spitting from my mouth with every sharp spasm. Melissa laughs lightly beside me, a soft, distant echo like a dream, and as the last breaths of smoke break from my lips every tense, nervous tick goes with them, lost in the swirling, sifting mist of Pauly’s living room.

Francie’s off of the couch, now, swaying slowly with the rolling, pounding bass in front Pauly, her hips tracing long, lingering rings in the drifting smoke. Pauly smirks knowingly and pulls another folded, paper wad from his sweats, sarcastically flicking twenty-dollar bills at her one after another that trickle down her body and form a loose green ring around her naked feet. Carefully, he slides a massive hand across the small of her back and draws her across his lap, and for a moment I can’t help a tinge of jealousy. Not because of her, but because of all this. I can’t see tomorrow through the sweet, hanging fog, and there’s a freedom in that. I’ve never seen a stack of bills like the one Pauly handed Tony, either, and there’s freedom in that, too.

And then there’s a hand on my leg. A coconut-buttered palm cupping my knee, and a pretty smile budding right next to me.

“So,” she says, quick like poetry. “How do you know Tony?” Could there be freedom in this, too?

“Freedom in capitalist society always remains about the same as it was in ancient Greek republics: freedom for slave owners.”

—Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

Whir. Click. Punch.

My rag fist massages the grease out of a hundred plastic discs, swollen knuckles gushing antiseptic froth. There’s no window in this cell, just the meager pulse of sunlight bouncing in from the kitchen sticking to the yellowed stone walls.

7:00.

It’s dim in the morning, enough that no one should be able to tell I’m wearing the same soap-stai

ned clothes from yesterday, enough that no one should be able to see the branching red veins crawling over the whites of my eyes, but no one’s looking back here, anyway. The smoke must still be lingering somewhere in my chest, seeping into my blood, drifting through my skull, because in the pale breaths of light, the dishes all wash together, a tired montage of grease and soap, crumbs and plastic. Soap, scrub, rinse. Tony’s laugh erupts from the register and echoes through the kitchen, a sudden brick of human expression against the mechanical drone of running water and rattling pans. How does he do it? That smile—that sprawling, sideways smirk—it never fades. It was there at 5:30 this morning, beaming over me from the foot of Melissa’s stiff, narrow mattress, leading me in hushed steps across the lightless room and past two soft, naked backs gently rising and falling in the plush blue carpet like a pair of sinking bodies. It was there last night, flashing in and out of view from behind the last bottle of rum, and it was the last glance of Tony’s face before it disappeared behind a black silk curtain of Jess’s hair.

“Oye, cabrón, we need the pans for the pizza oven, vamos!” Pizza pans, saucepans, salad bowls, metal sinks—life here is all framed in cold plastic faces and hard metal edges. But nothing at Pauly’s is so rigid, so determined. It’s beautifully impermanent; the high, the buzz, the soft warmth of Melissa’s lips branded to my neck, still lingering like a sunburn. That will fade, too, it all will. The sudden rushes of blood and chemicals, the fleeting bouts of ecstasy, they’re not meant to last. But I found something in that apartment I haven’t felt in two years in this kitchen: a pulse.

And there’s something else I found with Tony last night that I never could at Romeo’s. $150 an ounce, two ounces a night. If we start on Monday, I’ve beat next week’s paycheck by Tuesday, and if Romeo doesn’t like it, tough, because by Wednesday I can finally afford a pair of shoes that don’t hiccup pink suds with every step.

2:00. Lunch is another soggy egg sandwich I was supposed to pay for.

The Front of the Freeway

The Front of the Freeway